Organisation Todt

The Organisation Todt (OT) was a Third Reich civil and military engineering group in Germany named after its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior Nazi figure. The organization was responsible for a huge range of engineering projects both in pre-World War II Germany, and in Germany itself and occupied territories from France to the Soviet Union during the war, and became notorious for using forced labour. The history of the organization falls fairly neatly into three phases:

- A pre-war period from 1933–1938 during which Todt’s primary office was that of General Inspector of German Roadways (Generalinspektor für das deutsche Straßenwesen) and his primary responsibility the construction of the Autobahn network. The organisation was able to draw on "conscripted" - i.e., compulsory - labour, from within Germany, through the Reich Labour Service (Reichsarbeitsdienst, RAD).

- The period from 1938, when the Organisation Todt proper was founded until February 1942, when Todt died in a plane crash. During this period (1940) Fritz Todt was named Minister for Armaments and Munitions (Reichminister für Bewaffnung und Munition) and the projects of the Organisation Todt became almost exclusively military. The huge increase in the demand for labour created by the various military and paramilitary projects was met by a series of expansions of the laws on compulsory service, which ultimately obligated all Germans to arbitrarily determined (i.e. effectively unlimited) compulsory labour for the state: Zwangsarbeit.[1] From 1938-40, over 1.75 million Germans were conscripted into labour service. From 1940-42, Organization Todt began its reliance on Gastarbeitnehmer (guest workers), Militärinternierte (military internees), Zivilarbeiter (civilian workers), Ostarbeiter (Eastern workers) and Hilfswillige ("volunteer") POW workers.

- The period from 1942 until the end of the war, when Albert Speer succeeded Todt in office and the Organisation Todt was absorbed into the (renamed and expanded) Ministry for Armaments and War Production (Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion). Approximately 1.4 million labourers were in the service of the Organisation. Overall, 1% were Germans rejected from military service and 1.5% were concentration camp prisoners; the rest were prisoners of war and compulsory labourers from occupied countries. All were effectively treated as slaves and existed in the complete and arbitrary service of a ruthless totalitarian state. Many did not survive the work or the war.

Prehistory from 1933 to 1938: the construction of the German Autobahn network

The Autobahn concept did not originate with the Nazis but had its beginnings in the efforts of a private consortium, the HaFraBa (Verein zur Vorbereitung der Autostraße Hansestädte-Frankfurt-Basel), founded in 1926 for the purpose of building a high-speed highway route between Northern Germany and Basel, Switzerland. With a decree establishing a Reichsautobahnen project for an entire network of highways, issued on 27 June 1933, Adolf Hitler made it a vastly more ambitious public project and the responsibility of Fritz Todt as newly-named General Inspector of German Roadways.[2]

By 1934, the self-aggrandizing Todt had succeeded in elevating this office to near cabinet rank. Todt was, however, also an extremely capable administrator and had built by 1938 more than 3,000 km (1,900 mi) of roadway. The Autobahn project became one of the show pieces of the Nazi regime. Todt had also in that period put together the administrative core of what would properly speaking become the Organisation Todt. The growth and growing importance of the organization, and the increasing prominence of its leader, are a textbook example of the way in which an aggressive and able party leader could expand his authority and purview in the fluid (and treacherous) context of the polycratic German state under Adolf Hitler.[3]

Initially, the Autobahn project relied on the open labour market as a labour source. Germany was at this time still recovering from the effects of the Great Depression and there was no shortage of available labour. As the economy recovered and labour supply became a more serious issue, from 1935 Organisation Todt was able to draw on conscripted—i.e., compulsory—labour, in these years from within Germany, through the Reich Labour Service (Reichsarbeitsdienst, RAD). As per the law of 26 June 1935, all male Germans between the ages of 18 and 25 were required to perform six months of state service.[4] In this period too the work was compensated, at a rate slightly greater than that of unemployment support. The composition and working conditions of the labour force would change drastically for the worse over the course of the ten following years.[5]

1938 to February 1942: the Organisation Todt proper

In 1938 Todt founded the Organisation Todt proper as a consortium of the administrative offices which Todt had personally set up in the course of the Autobahn project, private companies as subcontractors and the primary source of technical engineering expertise, and the Labour Service as manpower source. He was appointed by Hitler as plenipotentiary for Labour within the second four year plan, undermining Goering's rule. Investment in civil engineering work was greatly reduced. Between 1939 and 1943, in contrast to the period from 1933 to 1938, less than 1,000 km (620 mi) of roadway were added to the Autobahn system. Emphasis was shifted to military efforts, the first major project being the Westwall (known in English as the Siegfried Line) built opposite the French Maginot Line and serving a similar purpose.[6] Correspondingly, Todt himself was in 1940 named Minister of Armaments and Munitions. In 1941 Todt and his organization were further charged with an even larger project, the construction of an Atlantic wall to be built on the coasts of occupied France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Included with this "Atlantic Wall" project were the fortification of the British Channel Islands, which were occupied by Nazi Germany from 30 June 1940 to 8 May 1945. The only nazi concentration camps on British soil were the camps operated by Organisation Todt in Alderney.

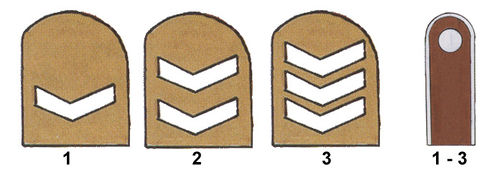

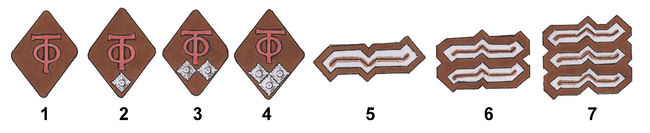

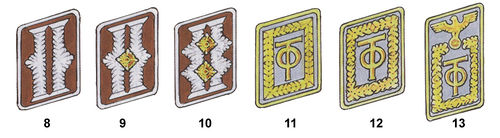

The huge increase in the demand for labour created by the Westwall project was met by a series of expansions of the laws on compulsory service, which ultimately obligated all Germans to arbitrarily determined (i.e. effectively unlimited) compulsory labour for the state: Zwangsarbeit.[7] Between 1938 and 1940, 1.75 million Germans were conscripted into labour service. Both the Organisation Todt and the Labour Service were characteristically paramilitary in hierarchy and appearance, with elaborate sets of chevrons, epaulettes, and other insignia for the display and recognition of rank.

Fritz Todt died in a plane crash on 8 February 1942, shortly after a meeting with Hitler in East Prussia. Todt had become convinced that the war could not be won and thought himself indispensable enough to say as much to Hitler. As a result, there has been some speculation that Todt’s death was a covert assassination, but this has never been substantiated. Todt was succeeded as Minister of Armaments and Munitions and de facto head of the Organisation Todt by Albert Speer.

1942 to 1945: the Organisation Todt under Albert Speer's Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion

Despite the death of its paladin, the Organisation Todt continued to exist as an engineering organization and drew multiple further assignments. At the beginning of 1943, in addition to its continuing work on the Atlantic Wall, the organization also undertook the construction of launch platforms in northern France for the V1 and V2 rockets. In the same summer, following the increasingly defensive course of the German war effort, the organization was further charged with the construction of air-raid shelters and the repair of bombed buildings in cities within Germany and with the construction of underground refineries and armaments factories (Project Riese).

Administratively, however, the organization was effectively incorporated into Albert Speer’s Ministry of Armaments and War Production in 1943. Speer’s concerns, in the context of an increasingly desperate Germany in which all production had been severely impacted by materials and manpower shortages, and by Allied bombing, ranged over almost the whole of the German war-time economy. Speer managed to increase production significantly, at the cost of a vastly increased reliance on compulsory labour. This applied as well to the labour force of the Organisation Todt.

By the end of the war, the compulsory state service for Germans had been reduced to six weeks of perfunctory military training and all available conscript German manpower diverted to military units and direct military support organisations. From the beginning of 1942 at the latest, their place was increasingly taken by prisoners of war and compulsory labourers from occupied countries. Foreign nationals and POWs were often, somewhat euphemistically, referred to as "foreign workers" (Fremdarbeiter). In 1943 and 1944 these were further augmented by concentration camp and other prisoners. Beginning autumn of 1944, between 10,000 to 20,000 half-Jews (Mischlinge) and persons related to Jews by marriage were recruited into special units[8].

By the end of 1944, of approximately 1.4 million labourers in the service of the Organisation Todt overall, 1% were Germans rejected from military service and 1.5% were concentration camp prisoners; the rest were prisoners of war and compulsory labourers from occupied countries. All were effectively treated as slaves and existed in the complete and arbitrary service of a ruthless totalitarian state. Many did not survive the work or the war.

Organisation Todt administrative units (Einsatzgruppen)

German (national) and foreign

- OT-Einsatzgruppe Italien

- OT-Einsatzgruppe Ost (Kiev)

- OT-Einsatzgruppe Reich (Berlin)

- OT-Einsatzgruppe Südost (Belgrade)

- OT-Einsatzgruppe West (Paris)

- OT-Einsatzgruppe Wiking (Oslo)

- OT-Einsatzgruppe Russland Nord (Tallinn)

Intra German

- Deutschland I ("Tannenberg") (Rastenburg)

- Deutschland II (Berlin)

- Deutschland III ("Hansa") (Essen)

- Deutschland IV ("Kyffhäuser") (Weimar)

- Deutschland V (Heidelberg)

- Deutschland VI (Munich)

- Deutschland VII (Prague)

- Deutschland VIII ("Alpen") (Villach)

Organisation Todt Administrative and Working Ranks

- Chef der OT

- OT-Einsatzgruppenleiter I

- OT-Einsatzgruppenleiter II

- OT-Einsatzleiter

- OT-Hauptbauleiter

- OT-Bauleiter

- OT-Hauptbauführer

- OT-Oberbauführer

- OT-Bauführer

- OT-Haupttruppführer

- OT-Obertruppführer

- OT-Truppführer

- OT-Oberstfrontführer

- OT-Oberstabsfrontführer

- OT-Stabsfrontführer

- OT-Oberfrontführer

- OT-Frontführer

- OT-Obermeister

- OT-Obermeister

- OT-Meister

- OT-Vorarbeiter

- OT-Stammarbeiter

- OT-Arbeiter

Sample insignia

Sample working ranks

Sample shoulder patches (in use until 1943)

Sample collar patches (used after 1943)

Notes

- ↑ Verordnung zur Sicherstellung des Kräftebedarfs für Aufgaben von besonderer staatspolitischer Bedeutung of October 15, 1938 (Notdienstverordnung), RGBl. 1938 I, Nr. 170, S. 1441–1443; Verordnung zur Sicherstellung des Kräftebedarfs für Aufgaben von besonderer staatspolitischer Bedeutung of February 13, 1939, RGBl. 1939 I, Nr. 25, S. 206f.; Gesetz über Sachleistungen für Reichsaufgaben (Reichsleistungsgesetz) of September 1, 1939, RGBl. 1939 I, Nr. 166, S. 1645–1654. [ RGBl = Reichsgesetzblatt, the official organ for he publication of laws.] For further background, see Die Ausweitung von Dienstpflichten im Nationalsozialismus(German), a working paper of the Forschungsprojekt Gemeinschaften, Humboldt University, Berlin, 1996–1999.

- ↑ Gesetz über die Errichtung eines Unternehmens Reichsautobahnen (German). Note that “law” is the literal translation of the German term, “Gesetz”, used in the text of this (and other) laws of the period. Given, however, that by this date legislative power had already been transferred to the executive (i.e. Hitler) primarily by means of the "authorization law" of 23 March 1933 (Gesetz zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich), this, and all other legislation of the Third Reich was effectively a purely executive order, i.e. a decree (Erlass).

- ↑ For an extensive discussion of Third Reich polycracy, see John Hiden, Republican and Fascist Germany: Themes and Variations in the History of Weimar and the Third Reich (1918–1945), Longman, 1996. ISBN 0582492106.

- ↑ Reichsarbeitsdienstgesetz (German)

- ↑ For additional general background on the Autobahn project, see Walter Brummer, Zur Geschichte der Autobahn. (German)

- ↑ One of the quasi-civil projects loosely associated with the Westwall project was the construction of the Hunsrück Highway (Hunsrückhöhenstraße, largely coinciding with the B327 and B407 in contemporary Germany). Its southern endpoint was near Trier, at the border with France and on the wall. The construction of the Hunsrück Highway forms the backdrop for the fifth chapter of Edgar Reitz’ film, Heimat (1984) and one of its central figures is a (fictional) engineer on the project.

- ↑ Verordnung zur Sicherstellung des Kräftebedarfs für Aufgaben von besonderer staatspolitischer Bedeutung of October 15, 1938 (Notdienstverordnung), RGBl. 1938 I, Nr. 170, S. 1441–1443; Verordnung zur Sicherstellung des Kräftebedarfs für Aufgaben von besonderer staatspolitischer Bedeutung of February 13, 1939, RGBl. 1939 I, Nr. 25, S. 206f.; Gesetz über Sachleistungen für Reichsaufgaben (Reichsleistungsgesetz) of September 1, 1939, RGBl. 1939 I, Nr. 166, S. 1645–1654. [ RGBl = Reichsgesetzblatt, the official organ for he publication of laws.] For further background, see Die Ausweitung von Dienstpflichten im Nationalsozialismus(German), a working paper of the Forschungsprojekt Gemeinschaften, Humboldt University, Berlin, 1996–1999.

- ↑ Wolf Gruner (2006). Jewish Forced Labor Under the Nazis. Economic Needs and Racial Aims, 1938–1944. Institute of Contemporary History, Munich and Berlin. New York: Cambridge University Press. Published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 9780521838757

Further reading

- Einsatz der Organisation Todt (German) (Historisches Centrum Hagen)

- Fritz Todt (German) (Deutsches Historisches Museum)

- Der Reichsarbeistsdienst (German) (Deutsches Historisches Museum)

- Robert Gildea, (2002), Marianne in Chains: Daily Life in the Heart of France During the German Occupation, Picador. ISBN 0-312-42359-4.